“Hi, all, I thought we were eating at one?” Dad said.

“The bird’s got a way to go – maybe another hour,” Nan said.

Mom mouthed to Dad a silent, “No way.”

I was a first class Mom lip reader.

Dad walked to the oven and opened the front.

“Jesus Christ, who are you feeding?”

“Shut your mouth,” Nan said.

“That prehistoric beast is the same size as Rory,” Dad said.

“Mind your business.”

Mom whispered to me, “Rory is smaller.”

“We’ll eat tomorrow,” Dad said.

“Another hour. Go inside and be useful.” Nan said, waving Dad away. “Get two folding chairs and bring my bag. I forgot something and need you to go to the store.”

Dad eyed me up and down. He wanted to send me but he thought I was getting sick. Resigned, Dad exhaled loudly, ensuring everyone in the balcony knew he was leaving the stage. Being at Nan’s cheered me up. Everything was big. She was big. Pop was big. The coffee cups were big. At her house, I could drink anything I wanted, when I wanted. Dad returned from the front room to the kitchen with Nan’s pocketbook. I could see his arm muscles working hard, lifting the heavy bag.

“Here you go. What do you need?” Dad said.

“Go down to Parker’s and get me a pound of butter.”

Dad walked to the fridge, opened the door and stuck his head in it. “You have a full pound.”

“I need six sticks for the mashed potatoes.”

“We’re six people! That’s a quarter pound of butter per person. Are you trying to stop our hearts with a single meal?”

|

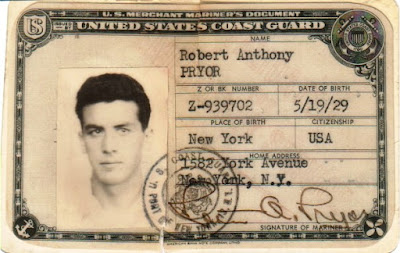

| 1582 YorkAve Parkers Grocery @1940 |

“I’m making mashed potatoes for the week and it’s none of your business. Get the butter.”

“And the thirty pound bird?”

“Don’t exaggerate. It’s twenty-six pounds.”

“Oh, only twenty-six. Let’s see, more than four pounds per person, that should cover our meat provision for our sea voyage.”

I was curious. Would Nan slap him or not? I was pulling for a slap. She seemed close. Instead, she stared him down. He wisely took the money and went to the store. I joined Rory and Pop in the living room to watch the end of the movie. Dad came back and stayed in the kitchen with Nan and Mom.

More than an hour passed.

“I’m starving. How much longer?” Dad said.

“I’ll take a look,” answered Nan.

I got up and watched through the doorway. Nan opened the oven and took the turkey out with her arms firmly hanging onto both pan handles. From behind, she looked like a Russian weightlifter. She placed the pan on the counter and checked the thermometer. Dad was right behind her.

“What does it say?” Dad said.

“135 degrees,” Nan said.

“Forget it, put it back in.”

“No, it’s done.”

“You’re nuts.”

“It’s fine, look?”

Nan sliced into the meat. It was pink like a flower.

“Meat should be 175 degrees,” Dad said. “That bird just stopped breathing.”

“That’s it. Let’s go.”

Nan said and moved the enormous pan toward the table. Dad met her halfway across the kitchen floor and began guiding her back toward the oven. They both had their hands on the pan’s handles. A turkey dance!

“Give it to me,” Dad said.

“Leave me alone. Start mashing the potatoes,” Nan said.

“Give it to me!”

He tugged. She tugged. The pan didn’t know what to do.

The pan flipped over. The gravy soared and the turkey smacked the floor. Nan was a mess. Dad’s shirt, slacks and new dress shoes with the little pinholes were no better. Stunned, Nan and Dad stared down at the the bird on the linoleum. Nan spoke first. “Ah shit, I’m lying down,” And she did.

She passed through the living room. Me frozen in the doorway and Pop with Rory on his lap. They watched like two wide mouth bass. I wish I could’ve taken a picture. Pop and Mom exchanged places. She joined Rory watching TV. Pop went to the kitchen and began to help Dad. They put the bird back in the pan with a couple of cups of water to replace the irreplaceable gravy and put the pan back in the oven. Pop gave Dad one of his extra large guinea tee shirts. Pop’s pants didn't fit Dad, so he gave Dad a pair of his giant boxer shorts. Dad wore Pop’s boxer shorts over his boxer shorts – that went nicely with his dark socks and skinny legs. I saw Mom peek in, point at Dad and start to laugh.

Sometime much later, Pop announced, “OK, everything is ready.”

He went into the front room and brought Nan back. She returned to the kitchen and took over as if nothing had happened.

“Bob, carve the meat.”

Dad grabbed the knife and did as he was told. This relieved everyone. The table comfortably sat six people yet with the large amount of food on it, it was hard to see each other. Everyone was scary polite. Late in the meal, Dad looked at the bucket of mashed potatoes and said, “You know from this angle I can see a goat circling the top of Potato Mountain.”

We all laughed except Nan. But she didn’t hit him. The storm passed and Rory and I started looking forward to our favorite Thanksgiving ritual – Pop watching. He was a gentle Smokey the bear and never yelled at us. After the meal, he drank two short glasses of Ballantine Ale, wiped his mouth carefully with his linen napkin, and said, “Thank you, excuse me.”

He lifted himself from the table, then walked from his kitchen chair to his living room chair. Once Rory and I heard “Swoosh,” Pop’s bottom sinking into the plastic, we started counting backward, “10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1…”

We peeked into the living room. Pop was sawing wood. Rory and I stared at him.

While Pop slept, a cartoon came on with two poor kids who go to bed with nothing to eat. They dream, people come and bring them goodies and music starts to play. Rory and I stood behind Pop’s chair on each side of his head and softly sung along with the cartoon song into his ears:

"Meet me tonight in dreamland, under the silvery moon.

Meet me tonight in dreamland, where love’s sweet roses bloom.

Come with the love light gleaming, in your dear eyes of blue.

Meet me in dreamland, Sweet dreamy dreamland,

There let my dreams come true."

Our singing didn’t wake him. Pop had a stretched out snore with three different sounds. Nan had a toy piano with eight color coded keys. You could play a full octave of tones. It came with a color-coded music book with classics like “Pop Goes the Weasel,” “Roll Out the Barrel” and “This Old Man.” Rory was pretty good on the thing – he played “Jingle Bells” with ease. He went over to the piano.

In between Pop's snores he’d hit a key. It sounded pretty good. Rory played around a bit until he located a couple of notes to harmonize with Pop’s snoring. Not wanting to be left out, not having Rory’s natural musical talent, I improvised. Nan’s toilet door made a creaking sound when you opened or closed it. I went over to the door and opened it a smidge to try to join the band. I found a funky “eek” and added it to the mix. Leaning over, looking back into the living room, I could see Rory. Once we made eye contact, it was easy to locate our rhythm.

We riffed, “Snore, piano key, eek; snore, piano key, eek.”

Our tune had a hook as Dad loved to say.

Mom threw a sponge at my head. I ducked. The band played on.

Sponge two was in the air.

I avoided it by doing the cha-cha.

“I will kill you both. Keep it up, I’ll kill you both dead."

Noticing Mom was out of sponges, and the next airborne item could be a spoon or fork, Rory and I left the airwaves.

Later on, Pauline and Charlie Hannah came over and started playing Pokeno with Nan and Pop. Dad and Mom moved to the sink area. I sat on the washing machine right next to them. Mom picked up a dish and started scrubbing it. Dad squeezed too much dish soap into the water, then started playing with the faucet’s screws.

“Let’s get this over with, you’re moping.”

“Not true. The secret is a long hot soak. Then the grease slides itself off.” Dad said and continued to play with the faucet.

“The secret is you’re full of shit and have a bony ass,” Mom said.

Nan got up came over to the sink and said “Leave the kids here – you can pick them up in the morning.”

She helped them gather their things and threw them out of the house.

Rory and I conked out together on one bed. The playful noise coming from the card game in the kitchen was the kind of yelling we could sleep through. The last thing on my mind as I drifted off was Santa’s sleigh flying over the 59th Street Bridge up York Avenue heading towards my house.

.jpg)